In everyday English, technology can refer to a gadget, artefact, know-how, or software application. In contrast to this colloquial understanding, Professor Brian Arthur[1] emphasises the importance of a broader understanding in which technology is seen as a means to harness natural phenomena and arrange processes to produce something or achieve a specific purpose.

To substantiate this broader understanding of technology, Brian Arthur[2] provides three different definitions of technology:

- The most basic definition is that technology (in a singular sense) is a means to fulfill a human purpose by harnessing natural phenomena. For some technologies, this purpose may be explicit; for others, it may be vague. As a means, a technology may be a method, process or device. A technology does something, it executes a purpose. It could be simple (a roller bearing) or complicated (a wavelength division multiplexer). It could be material, like an engine, or nonmaterial, like a digital compression algorithm. Some technologies combine with other technologies into technology architectures, which may form part of even larger technological systems. For example, an engine is part of a car, which is part of a more extensive transport system. However, an engine itself consists of an assembly of complementary technologies. Generating energy with a photovoltaic panel, using MS Teams/Slack/WhatsApp to coordinate a team or designing with computer-aided design (CAD) software are examples of technologies at this level.

- A second definition is plural: technology as an assemblage of related practices and components. This covers technologies such as electronics or biotechnology that are collections or toolboxes of individual technologies and practices. These assemblages can also be called bodies of technology as they harness related phenomena. Examples are the catalogue of ways alternative energy can be generated or how different sensors and control systems can be deployed in a manufacturing plant. When solving a problem, it is possible to choose between alternatives from this toolbox or different toolboxes.

- A third definition is technology as the entire collection of devices and engineering practices available to a society. As new technologies become available, new institutions, norms, and supporting technologies are needed to make them feasible. In other words, the economy expresses its chosen technologies.

Arthur argues that we need these meanings because each category of technology comes into being, and evolves, differently (Arthur, 2009:29).

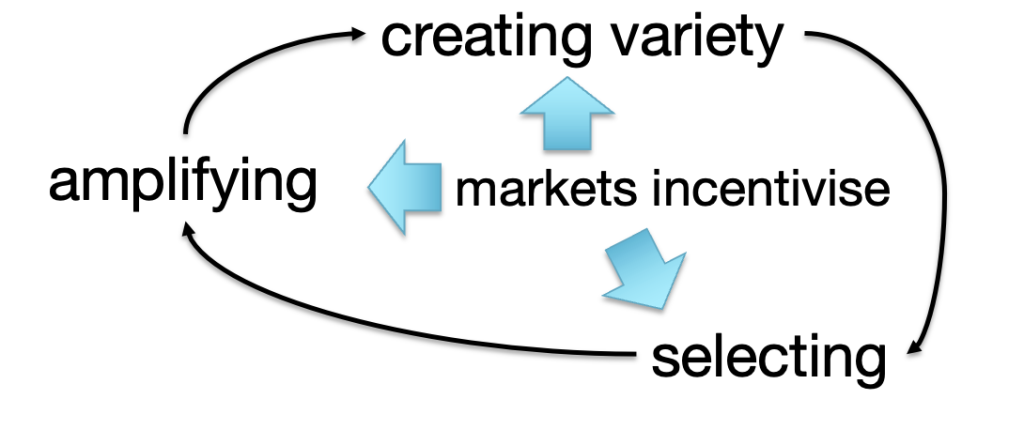

As technologies are absorbed or deployed, complementary technologies, including regulations, institutions, and norms, are deployed or developed. This is a process of structural deepening, where old technologies are increasingly substituted with new combinations of technologies and institutions, and industries, markets, and institutions adjust or reorganise.

These three definitions are shown in Table 1. Changes in the first category are relatively easy and fast, becoming progressively more difficult in the second and third categories. The third category is marked by an ongoing change process often carried over generations or extended periods.

Table 1: Definitions of technology

| Definition of technology | Examples | Relevance to tracking tech change |

| Technology as a method, process or device. | CAD software, Enterprise resource planning (ERP), Industrial robotics, recycling. | Identifying technologies that are affecting companies, or that require coordination beyond a single firm. |

| Technology as an assemblage of practices and components – toolboxes. | Digitalisation of manufacturing, greening of manufacturing, supply chain integration. | Identifying technologies that require many simultaneous changes in one or many organisations. Structural deepening would require coordination between industries and enabling institutions. |

| Technology as the entire collection of devices and practices available or the economy as an expression of its technologies. | The societal preference for greener solutions, a growing sensitivity towards the effects of mankind on nature, a new awareness of healthier living. | The structural change processes that shape what the economy is evolving towards as technologies, institutions and markets co-evolve. New institutions create the stepping stones to the future, while old institutions try to maintain the past. |

Tracking technological change at the first level is almost futile. This is where companies, or perhaps individuals in companies, procure or design a new solution that can solve a specific problem. This is hard to measure or track. People also describe their actions differently. I once met a CEO who called this R&D, while the financial director called it “investment” and the production manager called it “replacing something that we could no longer fix”.

As more and more people invest in a given technology, an assemblage or toolbox starts to develop. As time goes by, more and more technologies in this toolbox can connect with each other as standards and common sub-modules are developed. Alternative technologies that approach the same problem or draw from the same principles will emerge. The result is that companies can choose different configurations of related technologies within the same industry or market. However, it is also possible that companies can choose from different toolboxes in the same industry. Service providers that can help companies choose alternatives or implement solutions enter the marketplace. Enabling institutions that provide technological services, shared infrastructure, or education programmes may emerge around the technological toolboxes. A new technology language has formed. From a measurement perspective, tracking this kind of change in economic statistics is tricky because the changes are still mainly within companies, and economic statistics tend to lump all of the companies in a sector together. The implication is that while the first level of technological change is too detailed, the second level may be too generic.

One point is worth expanding further. Even if a new technological assemblage is available and well supported, some companies or industries might be unable to reach it. This is mainly because the new competencies required might be too far from what they have in place, and adopting these new competencies would require a completely new business model. These companies might actively resist and advocate against the new technological paradigm, but resistance might simply delay the inevitable.

At the third level of technology, the society and the core technological arrangements that make it distinct needs to be considered. At this level, it is not only about the technologies, but also the web of enabling institutions, social norms and markets that shapes the everyday choices of consumers, investors, businesses and the government. For instance, you could compare the public transport options in the Netherlands with those in South Africa and describe the differences in technological terms. At this level, it is again easy to identify the technologies, but it is hard to figure out how to replicate the outcomes or the pathways that led to a certain outcome.

[1] Arthur, W.B. 2015. Complexity and the economy. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

[2] Arthur, W.B. 2009. The nature of technology: what it is and how it evolves. New York: Free Press.

This blog was first published on the TIPS Technological Change and Innovation System Observatory website.